[This information is from pp. 73-80 of Shovel Ready: Razing Hopes, History, and a Sense of Place: Rethinking Schenectady's Downtown Strategies, a master's thesis in city planning by Christopher Patrick Spencer (MIT, 2001), and is reproduced with his permission. It is in the Schenectady Collection of the Schenectady County Public Library at Schdy R 711 Spe.]

Nothing is more sad than the death of an illusion.

Arthur Koestler

The dialog for the redevelopment of the 22 Block area east of city hall, heralded as "one of the most important moves in city's history" had started well before the original application had been filed with the state's Municipal Housing Authority [MHA] on October 1, 1946. (1) The initial goal that the city seemed to be trying to reach was to collect more in property tax in the downtown area. But early in the process, the goals began to shift — and continued to shift throughout, not to fit the problem, but to fit the criteria of the state and federal urban renewal programs. Therefore, many of the goals that the program later espoused may have been mere justifications for the program's existence. Perhaps it could be argued that the motivation for taking advantage of these programs was because they offered a way to help increase the revenue collected by the city in property taxes near the downtown. Slum clearance assisted by both the state and federal governments was just a tool to achieve this. A review of the project reveals that few of the goals that eventually became part of the plan such as increasing business for the downtown, creating a secondary business district, or improving the lives of the people living in the area, were ever attained or impossible to measure. Few understood back then the price that "free" big government money would place on both the residents who lived there and those who now have to deal with the impact it has had on the form and function of that part of the city. By foregoing state and federal money with the many strings attached, the city might have discovered a different path to realizing their original goal, as well as many of the subsequent goals that were not part of the project's early motivations. And in doing, the city would have been able to add to the story of a once proud neighborhood, rather than erasing it and starting from scratch.

Project Goals or Motivations

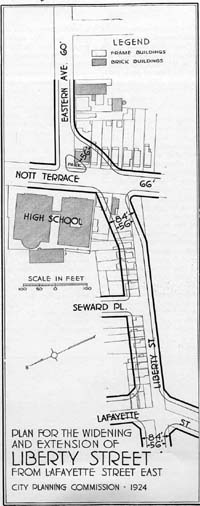

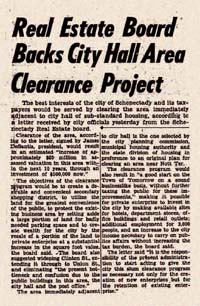

Fig 6.02 [enlarge]

Newspaper clipping showing "Real Estate Board Backs City Hall Area Clearance Project."

Slum or Blight Removal

The lack of specifications for classifying properties as standard or substandard provided an opportunity for cities to determine this based on goals that were unrelated to housing. In many cases, this led to a double standard being applied. "An official who is interested in speeding up the process of an urban renewal project may be tempted to apply high housing standards in order to justify the condemnation of part of the city, and, later on, to apply low housing standards in order to justify the quick relocation of displaced people." (2) When the loose standards are combined with the notion of planning blight, it makes a determination of the property conditions prior to the early proposals of the mid-1940s uncertain. People's recollections of the neighborhood that encompassed the 22 Block area varies, with those who recall it from the late 1940s more likely to refer to it as "a real nice neighborhood" while those whose recollections are from much later tend to describe it as a "run-down" section of the city. Photographic evidence from the early 1940s seems to indicate a different neighborhood than what is depicted prior to its removal over ten years later.

Improving the Tax Base

The promise of strengthening and even increasing the tax base was perhaps one of the most influential factors which led cities to engage in urban renewal programs. "The thought of bright and orderly new buildings pouring tax revenues into the city treasury [was] too much a temptation to resist." (3) The Real Estate Board in Schenectady in 1950 estimated that clearance of just the state funded projects within the 22 Block area "would result in an estimated increase of approximately $20 million in assessed valuation in this area within the next 10 years." (4) The final building on the site was not constructed for another 15 years, and overall, the site was never developed to the extent anticipated. If we take the following factors that are typical of these projects into account it seems unlikely that the project ever had the tax benefit that the city had built its hopes on:

- The assessed value of properties was often lowered prior to the cities trying to purchase or condemn them, to decrease the amount they would have to pay for them. This lowered assessment had the effect of lowering the amount of taxes collected prior to acquisition of the properties.

- As the conditions of the neighborhood deteriorated, tax assessment may have also decreased — effectively lowering what the city could collect.

- After the properties were taken or purchased, no taxes were collected on the properties until after they had been purchased or redeveloped.

- Overall the area was never developed to the density or level planned, creating a gap between what cities had anticipated the taxable value of the land would be and what it actually ended up being.

As Martin Anderson explains in the Federal Bulldozer: A Critical Analysis of Urban Renewal, 1949-1962 "Taxes are not paid on nonexistent buildings, and when the urban renewal bulldozers sweep through an area of the city, the tax revenue to the city decreases by the amount of taxes that were previously paid on the demolished buildings." (5) Another consideration is how the value on the land might have changed if the properties had undergone renovation rather than removal. While many cities were using urban renewal money to drastically change land-use near the core, other cities, such as Providence, Rhode Island, backed by its landmark study, College Hill: A Demonstration Study of Historic Area Renewal, began to find ways to use urban renewal funds to revitalize neighborhoods.

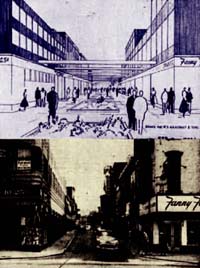

Fig 6.03 [enlarge]

Scenes like this were shown in the local newspapers at the time to show some of the bad existing conditions, but there were few scenes shown of the good and more typical conditions.

Improving the Lives of the "Slum Dwellers"

It was clear that for the hundreds of families living in the 22 Block area this was their neighborhood and their home. They did not consider it a slum and the majority of them wanted to stay. Unfortunately, no record was made of where each family was relocated to and no interviews were conducted at the time to determine if these people felt their conditions or lives had improved. Therefore, city officials had no way of measuring whether they had achieved this goal. But with all the properties gone, it is obvious that the city did at least meet its goal of removing what it considered, for its own purpose, "substandard" housing in the area.

For those residents who were moved to Yates Village, a newly constructed MHA housing project, its location over 2 miles from their former neighborhood left them isolated from their jobs and the conveniences of the downtown. With no public transportation or car for many of them, it was an area that offered little in the way of opportunity. For those businesses that had been displaced, some relocated while others closed up for good. But many of those that opened up show somewhere else, they were separated from their loyal customer base, making the relocation even more difficult. Many, however, were unable to find another area with the rents they could afford. For those that had lived above their shops, Yates Village and many of the other residential government solutions did not provide that mix or type of opportunity.

A New Business Street and an Expanded District

Fig 6.04 [enlarge]

During and after the urban renewal of the 22 Block area much of the rest of the downtown was looking to freshen-up the façades. Image shows the corner of State and Jay Streets. Note the added width given to the street in the architects rendering. (Jay Street is now a pedestrian mall.)

Schenectady's downtown in the late 1940s was still bustling enough to prompt those involved in the urban renewal project to use the Yogi Berra logic that no one goes there anymore because it's too crowded. An expanded business district and the creation of a new business street parallel to State Street, they thought, would help relieve the congestion and bring more people downtown. But as Schenectady historian Larry Hart writes of the decade of 1950-1960:

The downtown length of State Street, devoid of trolley tracks for the first time in more than a half century, was completely repaved with macadam by 1952. This gave Schenectady's old shopping core a fresh, clean look and prompted many store owners to install modern façades on their establishments. They all anticipated a bright busy future. It was all very deceiving. (6)

By the time plans were underway in the early 1950s, it was obvious that the downtown business was starting to decline. The logic had changed; the planners now insisted that this new business district would help the existing businesses and that they would get a share of this expected new influx of shoppers. Franklin Street, which was supposed to be the new secondary shopping street was eventually developed, but mostly into small office buildings. This was partly due to the faulty assumptions of the development pressure that was expected but never transpired, but also a manifestation of the changing retail model — from shops along the street to the isolated, stand-alone center with its vast acreage of parking. The only major retailer in the redevelopment area, Two Guys, was a few blocks away from the main axis of the downtown. It was situated with its parking lot away from the downtown, acting as an edge to the residential neighborhoods nearby and far enough away to be of no use to downtown shoppers. The planners had not expanded the business district, but created a separate one and diluted the existing one. It was never part of the "downtown scene" and probably never had the draw from the 50-mile radius that some of the developers had envisioned. Because of the many developments like it in the suburbs, it is unlikely that it ever brought suburban shoppers downtown, but at most it may have provided an alternative to those who would otherwise have had to venture into the old downtown.

Street Widening and Construction

One of the few goals that was reached in the city's main urban renewal area was to widen the streets, and expand the circulation network, traffic volume, and speed through the area. A number of streets were widened or extended while others were discontinued and a few new ones created. The new widths of these streets were based on expectation of future growth and traffic, despite the fact that the city had been losing population since 1930. The streets in that area have never carried the traffic that they were intended for. Their treeless edges and low-intensity bordering uses have created an environment that does not invite pedestrian usage. In recent years the city has tried to address this problem and now intends to plant trees and improve the landscaping of the area. It is hoped that those measures will create a linkage, inviting people from the surrounding neighborhoods to walk downtown. Not only did the urban renewal project not expand the downtown, it created a hard edge further isolating it from other residential areas rather than a seam binding or weaving them together.

Considering a Different Approach

Many felt that the demise of that neighborhood was inevitable and that given the downhill direction of the neighborhood at the time, the city really had no choice. If they did nothing, some felt, the neighborhood would decline further, spread blight into the downtown, and shoppers would leave the downtown for the malls. In the end, the city tried to remove the "cancer" of blight, but the downtown continued to get sicker, and the shoppers continued to avoid the city and frequent the new suburban malls anyway.

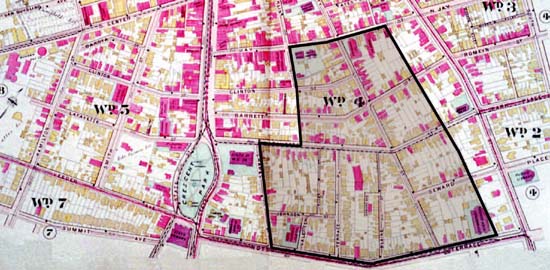

Fig 6.06 [enlarge]

1905 atlas showing the area around City Hall and much of the fine grained neighborhood of the 22 block area before urban removal and redevelopment.

The original goal of the city was to increase the revenue taken in through property tax in the downtown area. If the city had decided that the low taxes collected in the 22 Block area was the problem they had several alternatives. One was the route they took, which was to remove the structures in the area and essentially alter the land use. Another would have been to raise the tax rate that was already under attack as being too high. The third alternative, which does not seem to have been considered, would have been to develop strategies to improve the structures and upgrade the value of the area, while retaining its fine-grained texture and land-use patterns. Besides increasing the tax revenue for the city from that area, this approach might have had a number of other positive effects and prevented negative ones from occurring in addition to meeting the overall goals:

- By building up the neighborhood and helping it to revitalize from within (incumbent upgrading), it would have meant that those who remained would have had a higher quality of life than before. And although some would likely be displaced, a slower process would have reduced the amount of gentrification. In addition, for those residents who owned their homes, the upgrading and improved values would have increased their options and improved their "buy-out" if they chose to relocate as compared with the "planning blight" that reduced their home's value it and forced them to relocate.

- By strengthening the neighborhood around the downtown, it would reinforce the seam between other outlying neighborhoods and the downtown. This would encourage more pedestrian traffic through this neighborhood and into the downtown without adding to traffic or parking problem.

- The retention of this as a residential neighborhood would help ensure that the downtown remained compact and walkable, rather than spread out and more accessible by car than foot.

- Nearby employment opportunities and close services would benefit residents and add to the quality of life. For those who could not afford a car, this would remain a convenient place to live, shop, and work.

- The surrounding residents would add to the daytime activity and help support businesses in the off-peak hours when office workers or others are not around.

- The surrounding residential neighborhood would also reinforce the residential character within the downtown. For those living above the shops, it would prevent them from feeling like an island in a sea of commercial activity and isolated from the rest of the city's residential neighborhoods.

- Those living in and around the downtown would add to the viability of nighttime businesses and add to the safety for others who might come into the downtown during the later hours for shows, movies, or other forms of entertainment.

- The residential area in and around the downtown would provide a convenient workforce both for local industry and merchants. The proximity would allow them to access these opportunities of employment without further taxing the traffic or parking in the area.

- Given these benefits, the downtown would be able to differentiate itself from the new malls and provide a number of shopping and residential experiences that would be unique. By encouraging residential living in and around the downtown, the city would minimize the need for extensive road widening projects and parking lots.

- The retention and improvement of housing would cut down on the amount of new housing that would have to be built for displaced residents.

The logic of this is obviously clearer from the perspective of our time than it was back then. In thinking about it another way, it's easy to see that many of the things the planners and leaders of that era did, we would want to undo in order to build and strengthen the areas around the downtown to help revitalize the core. But this story is more than just a lesson of the need to set clear goals and ensure that all the objectives and strategies lead towards those goals; it is also about envisioning the outcome, understanding its impact on the surrounding areas, and considering all the options. Changing the objectives and rationalizing new goals to meet the demands or guidelines of federal or state programs only serves to prevent the city from reaching its original goal and ensures that the outcome will be unpredictable. Despite the promises and proclomations of the Town of Tomorrow and all those who pushed for the redevelopment of 22 Block Area, it was clear that there never was a consistent articulated vision for it. The only thing that was clear was that the Town of Tomorrow would forget about yesterday and leave nothing for today.