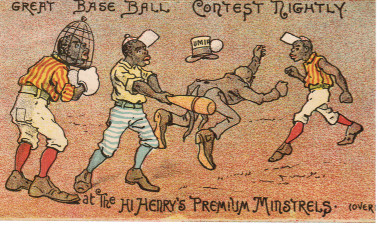

Set H 804-5 concerns baseball and blacks as do some individual trade cards. These black baseball trade cards are little different from many other 19th century trade cards depicting blacks. They show jolly, happy blacks having a good time although a more critical observer may easily describe them as demeaning rollicking buffoons. Frequently the blacks appear foolish and ludicrous but then many of the whites on baseball trade cards also appear as caricatures. These black trade cards are definitely correct in one thing. Blacks were playing baseball during the 19th century.

The First Black Major League Player

Jackie Robinson in 1947 was the first black baseball player in major league history. Right? No, wrong! Moses Fleetwood Walker, a catcher, was the first black major league player in major league history. Fleet Walker played for Toledo in 1884 in the American Association, then considered one of the two major leagues. Walker had attended Oberlin College and the University of Michigan before becoming a professional player. During that 1884 season, Fleet Walker played in 46 games compiling a .251 batting average. Walker's younger brother, Welday, also played in five major league games as an outfielder when the Toledo club was in need of a substitute due to injuries of regular players. Jackie Robinson, then, was the third black major league player — although the first in the 20th century.Squeezing Through a Closed Door

Blacks often did what most whites did in the United States and, during the 19th century, that included playing baseball. First, they did so in pick-up games in schoolyards and at picnics in hamlets, towns and cities. Later, they did so in formal organized baseball leagues. However, there was always the matter of segregation and racial prejudice to be considered if blacks were to play with whites from the very beginning. Harold Seymour in his research points out that in 1867, only two years after the Civil War, the early pioneering rule-making National Association of Base Ball Players ("organized baseball") meeting barred black players and teams from membership.

"It is not presumed by your Committee that any club who have applied are composed of persons of color, or any portion of them; and the recommendations of your Committee in this report are based upon this view, and they unanimously report against the admission of any club which may be composed of one or more colored persons."

Despite this 1867 resolution, a few black players managed to "squeeze through" the closed door. The Walker brothers played in the major leagues briefly in 1884. Some three dozen or so black players managed to perform in organized baseball's minor leagues during the late 19th century. First was John (Bud) Fowler who, ironically, was raised in Cooperstown, New York. Fowler had a long playing career that occasionally took him into recognized organized white leagues including the International League in 1887. He is noteworthy though because, in 1878, he was the first black player on an organized white team.

The International League — 1887

A number of black players concentrated in 1887 in the International League, then probably the highest caliber minor league. In addition to Fleet Walker and Fowler were Frank Grant, George Stovey and Bob Higgins. Grant was probably the best black 19th century player. He was certainly one of the best Buffalo players in 1887 and 1888 as he batted .366 and .346. Stovey and Higgins were pitchers in 1887 with Newark and Syracuse respectively. Their win-loss records reflect their ability. Stovey was 33-14 and Higgins finished the season with a 20-7 log.

These black players were treated harshly at times by opposing players, restaurant and hotel operators, as well as their own teammates. The Sporting News in 1889 reported,

"Last year they (Buffalo players) refused to have their picture taken on Grant's account and objected to traveling with him. The boys acknowledge that he is a good player, but they are in rebellion just the same."

The newspaper later commented that "about half the pitchers try their best to hit these colored players when (they are) at bat. One of the International League pitchers pitched for Grant's head all the time." Sporting Life credited the invention of shin guards, not to a catcher, but to the black second baseman Grant who constantly had to avoid sliding runners whose intent was to maim. Grant's experience was typical. The snubs, the cruel remarks, the bean balls, the slashing spikes made professional baseball a most difficult endeavor for blacks in "organized baseball."

Amazing as it may sound, four all-black teams represented four cities for all or part of a single season in recognized minor leagues. The cities were Trenton, New Jersey (1889); York, Pennsylvania (1890); Ansonia, Connecticut (1891); and Celeron, New York (1898). Northern local white fans usually rooted for their local team — even when blacks wore the local uniform.

Cap Anson's Influence

Local papers and some fans as well as the two national baseball papers sometimes wrote supportive articles of the black players but to no avail. Most white players, northern as well as southern, did not want black presence on the field. The International League Board of Directors met on July 14, 1887 and banned the signing of any more "colored players" in the future. A few days later, Cap Anson and his Chicago team played an exhibition game in Newark, New Jersey. George Stovey was to pitch against the major leaguers. Intolerant Anson refused to let Stovey play. Later, the influential Anson was instrumental in stopping New York's acquisition of Stovey, thus keeping blacks out of the major leagues.

Blacks were not welcome in white "organized baseball." But, like white America, blacks wanted to watch and play baseball. So they did — among themselves. That accounts for the ultimate origins of all-black teams and leagues, mostly during the 20th century, where "only the ball was white."